Keels come in a wide variety of shapes and sizes, but choosing the right keel for your needs can be easier said than done! Credit: KenWiedemann

What is a keel?

First things first, what is a keel? Before I fully understood the topic, I often described the keels on my bilge-keel yacht as the “legs” of the ship, but I would probably have been more accurate to describe them as the “spine”: just like the human spine keeps the backbone upright and links and supports the body, the keel is the primary structural part (and backbone) of a vessel, and every other main structural component of the boat will be directly or indirectly connected to it (although, of course, it’s worth mentioning that keels, unlike spines, are solid!). There are two major functions of a keel. One, to keep the boat balanced in the water. Two, to stop you going sideways when travelling under sail.How do keels work?

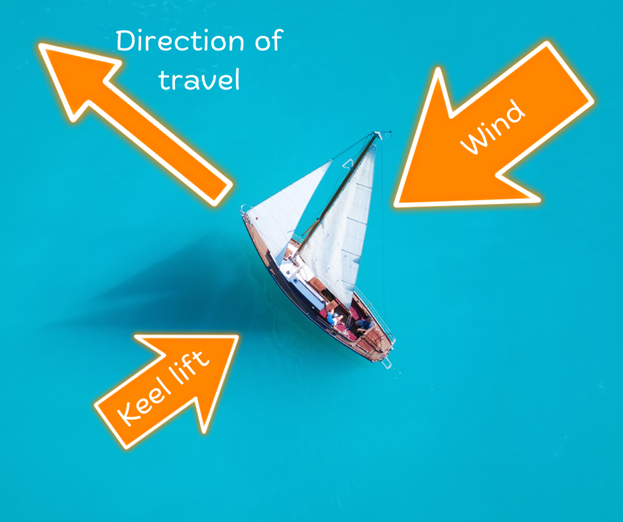

If you think that sailboats travel when pushed by wind… You’re not wrong, but wind and sails are only part of the story! To understand keels, we must first understand a little about sails, and how the opposing force of the wind on the sail works against the pressure on the keels to propel a vessel in its desired direction of travel. When a vessel is travelling under sail (that is, travelling forward due to the force of the wind on the sail) in anything other than direct downwind, the force on the boat is effectively pushing it slightly sideways, in accordance with the angle at which the wind is hitting the vessel.

Credit: @Writingandsailing

So, how do boats move forward rather than sideways?

Well, this is where the keels come into place. Much like an aeroplane’s wings, keels are “foils”, which basically means they utilise a special shape to guide the water around them, generating lifting force to make the boat move in its desired direction. But, unlike aeroplane wings, which are asymmetrical to force the air to push the plane upwards, keels are usually symmetrical, which allows the keels to generate lift on either side, in either direction, depending on what the wind is doing. This means that, when you’re travelling in any direction other than dead downwind (wind directly behind you), the wind is actually hitting your boat at an angle, producing lift on one side. This angular lift from the sail means the water is hitting the keel at an opposing angle, creating an opposing lift below the surface. These forces combine to push the boat forward. Without a keel, the wind would be the only force acting on the boat, meaning you’d start drifting to leeward (in the direction the wind is blowing), rather than forwards.But keels are so much smaller than sails; how do they produce sufficient opposing force?

The simple answer to this has to do with the density of the water. Water is over 800 times denser than air, meaning a small foil under water can produce an intense force. To put this into context, think about running on land vs through water – you can run a lot faster through the air than you can when waist-deep in water. Similarly, a comparatively small keel can produce plenty of lateral resistance to counteract the wind force in a large sail.What happens when you start heeling the boat?

Heeling the boat brings an additional layer of complexity to how the keels help propel the vessel forward. When heeling, the boat is at an angle, so the keel lift has a horizontal and vertical component, but only the horizontal counteracts the leeway. So, as you tilt your boat to the side, you start losing the efficiency of your keel.- At a 10° heel angle, the keel is around 94% effective

- At a 20° angle, the keel is around 90% effective

- At 30°, the keel drops to 87% effectiveness

- At a 45° angle, the keel will only be 71% effective

Contrary to some opinions, boats actually sail most effeciently below a 25° heel angle. Any more than that and you start to lose lateral force from the keels. Credit: mbbirdy

How do keels help with balance?

In addition to providing lift to help propel the boat forward, keels also provide ballast, or weight, to the bottom of the boat. This helps keep the boat upright and stops it from tilting too far over in rough seas and windy conditions. You need weight under the water line level to help balance the boat against the forces being applied to the sails, mast, rigging, etc., above the water line (basically anything creating windage that wants to roll the boat over). It may help to think of keels as half of a seesaw, with the other half being the mast and sails. As force increases on the sails, the weight of the keel must counteract it to keep your vessel upright and moving forward. And here, balance is achieved.Types of keel

Now we know a little about how the keels help propel a sailboat forward, it’s time to consider the different types of keel available. While all keels do a similar job, the shape, size, and design of different keels will affect your sailing performance. Whether you’re a coastal hopper, long-distance cruiser, or racer, the keel configuration of your boat will influence how you can use your boat.Fin keels

Fin keels are probably the most common examples of keel configuration when it comes to sailboats. A fin keel is a narrow plate fixed to the midship of a boat, projecting downward. It may look like the fin of a shark or other fish, but on the bottom, rather than the top, or like the wing of a plane. Like all keels, fin keels perform essential functions of keeping the boat balanced, so they’re usually made of heavy materials such as encapsulated iron or lead. They may be straight all the way down, or have a bulbous shape at the bottom. This will affect handling and how the boat responds in different weather conditions and sea states.Pros

- Excellent manoeuvrability as the keel is in the centre of the vessel

- Hydrodynamic shape reduces drag and allows for faster sailing

- Very efficient at preventing leeway

Cons

- Cannot take the ground without the support of a wall or harness

- Large size increases draft, meaning you will need more water to float and must be more vigilant in shallows

- Less effective at course-keeping than full keels

Fin keels are single keels bolted onto the bottom centre of a boat’s hull. Credit: omersukrugoksu

Full keels

A full keel, or long keel, extends along the entire length of a vessel, from bow (front) to stern (back). Rather than being bolted on, a full keel is a downward extension of the boat’s hull. Like other keels, a full keel will be incredibly heavy to help with balance and lateral resistance, and is particularly good for long-distance voyages as the size and shape of a full keel gives it better directional stability in rough water and when sailing downwind. However, this can be at the cost of manoeuvrability.Pros

- Excellent balance makes for comfortable passages even in rough conditions

- Stretching the entire length of the boat can reduce tipping fore and aft (not just port or starboard)

- Being part of the hull rather than just bolted on reduces the risk of damage – full keels won’t ever fall off!

- Offers extra strength and stability to the vessel

- Less sensitive to wind gusts

Cons

- Like a fin keel, full keels cannot take the ground without support from a wall or harness

- Great in a straight line, but less manoeuvrability, so not as good for coastal hopping or navigating marinas, for example

- Particularly bad when trying to reverse, only wants to travel forward

- Slow overall boat speed vs lighter configurations

Full keels travel the length of the boat and are built as part of the hull. They’re best for long-distance travelling in a straight line, and are often found on large ships such as ferries and tankers. Credit: @Writingandsailing

Bilge keels

Bilge keels, or twin keels, are a little like fin keels in that they’re bolted to the bottom of the boat, and are often a similar shape. However, where a fin keel is one keel in the centre of the hull, bilge keel boats have two keels that sit almost like legs beneath the boat. This means that bilge keelers can take the ground and stand up on their own, without the need for additional support from a harness or harbour wall. Bilge keels also usually have a shallower draft than fin keels, making them perfect for coastal hopping, river cruises, or other sailing where you might need to navigate shallow waters.Pros

- Able to take the ground without any support

- Shallow draft allows the boat to travel in shallower water

- Excellent for reducing rolling and heeling

- Best for coastal cruising – particularly in the UK!

Cons

- Not as fast as single keel designs

- Will loose lateral lift faster when heeling

- Increased ‘wetted surface’ can produce additional drag at low speeds

Bilge keels (like Sudana) have two keels that act like legs to allow the boat to stand up when out of the water. Credit: @writingandsailing

Lifting keels

If you want the performance of a fin keel combined with the ability to get into the shallow waters of a bilge keel, a lifting keel might be the answer. This type of keel is usually more like a fin in appearance but has the ability to be raised inside the boat to reduce draft when sailing in shallow water or taking the ground. Sailors might also consider a swing keel, which is effectively the same design, but (as the name suggests), this type of keel will swing into the hull, rather than lift into it vertically. It’s worth noting that a swing keel, unlike a lifting keel, will not retract 100% into the hull, so you will not be able to take the ground with a swing keel.Pros

- Able to be set at various depths, so can be adaptable for deep-sea and shallow-water sailing

- Easy to launch from a trailer

- If caught on a sandbar, the keel can be raised to allow the boat to drift off

- Like bilge keels, lifting/swinging keels are great for coastal cruising where you’ll be sailing in both deep and shallow water

- Lifting keels can dry out without the need for additional support

Cons

- Requires hinges and lifting tackles to operate, meaning there are more aspects that can fail and require maintenance

- Damage is more likely if a lifting keel runs aground accidentally vs a more traditional keel

- Can cause annoying knocks and rattles if not fitted correctly

- The housing the keel lifts into can significantly reduce living space inside the boat

- A swing keel cannot safely dry out unsupported

Lifting keels can be an excellent compromise for sailors who want the stability of a longer keel for off-shore passages, but would also like to explore shallower areas. Credit: @Writingandsailing

Daggerboards and centreboards

Similarly to lifting and swing keels, the main difference between a daggerboard and a centreboard is the way the keel lifts – a daggerboard is lifted vertically into a ‘trunk’ in the centre of the hull, while a centreboard pivots and can be set at different angles. Unlike other forms of keels, daggerboards are generally locked in place by a clip or pin, meaning they can be removed from the vessel entirely, and will be much lighter than more traditional keel types.Pros

- Can be sailed in shallow waters

- Able to lift/pivot the keel if it strikes an object or accidentally runs aground

- Lightweight with little drag (and drag can be further reduced by retracting the keel when not needed)

- Easy to launch from a trailer

- Most often found on lightweight vessels like sailing dingys that can be easily single-handed

Cons

- More likely to get damaged if not retracted before hitting the ground or obstacles in the water

- Often made from wood which can rot over time

- More moving parts mean more potential for failure/damage

- Lightweight and may need extra ballast to counteract strong winds

- Not suitable for offshore cruising

Leeboards

Like daggerboards, leeboards are attached to a vessel on a pin, and pivot in/out of the water as required. You’ll most commonly find leeboards on vessels like Dutch barges, with a leeboard on both the port and starboard side of the ship. These are lightweight ‘fins’ that won’t provide ballast and only help with leeway drift; ballast is added into the bottom of the hull to keep the boat stable. When needed, leeboards will be dropped on the leeward (the side of the boat the wind isn’t touching) side of the boat, and the pressure of the water/wind will push the leeboard against the side of the hull to stop sideways movement, while the leeboard on the windward side of the vessel is raised on a block and tackle and secured in place.Pros

- Usually found on large, flat-bottom vessels like Dutch barges, to help reduce leeway drag in heavy winds

- Can be easily raised/lowered as required

- Enables a flat bottomed boat to access very shallows areas and not run aground

Cons

- Not generally suitable for sailing vessels that require consistent ballast and lateral resistance beneath the water

Leeboards are often found on flat-bottomed boats, like Dutch barges, and can be lowered on the leeward side to help maintain course in strong winds. Image credit: @writingandsailing

Does it matter what size your keel is?

For the sake of the rest of this article, we’ll only focus on fixed keels, which are most commonly found on monohull sailing vessels. Regardless of the type of keel you have, the size and shape of the keel will also influence how the boat performs and what you can do with it. For example, a deep keel will obviously affect how much water you need underneath the boat in order to float, which is a particularly essential consideration when sailing around the UK, which is renowned for shallow waters, sandbanks, and a very large tidal range. The length of the keel will also affect its performance. A long keel that extends the full length of the boat will be fantastic at reducing leeway drift, but will produce more drag that can make it harder to manoeuvre in tight spots or to steer the boat in reverse. On the other hand, a thinner, shorter fin or bilge keel will offer less resistance and may allow the boat to travel faster and be more responsive when turning or reversing. But this has the trade-off of producing less lateral force, so you may find your boat drifting leeway by a degree or so if you don’t counteract it with vigilant steering. Where the weight is in the keel is also important to consider. A bulb keel (which has a bulbous shape at the bottom of the keel), for example, is generally long and thin, with ballast at the base that keeps the weight lower. This design is often used for performance vessels, like racing yachts, as the lower ballast allows the boat to be lighter and minimise drag without sacrificing balance. You may notice that the thickness of the keel is another aspect that influences sailing performance. While a thicker, heavier keel will be better for stability and preventing leeway drift, it will also make the boat heavier, slower, and potentially harder to handle.What is draft and how does this come into play?

As we’ve seen above, the size of a ship’s keel will influence the sailing performance. But what does this have to do with draft? Well, a boat’s draft refers to the distance between the waterline and the very bottom of the keel. In other words, it tells you how much water your boat needs in order to float. This doesn’t mean your draft is the same as your keel depth, as draft will also include the part of your hull that sits beneath the water in its measurements.Why do I need to know my draft?

Knowing your draft means you know how much water you can float in. This is particularly important when accessing marinas, which may have sills or other obstacles that make them only accessible in certain tides. It’s also useful when anchoring, as you can compare your draft to the tide height to know whether you will dry out or remain floating.

If you don’t know your draft, you won’t know how much water you need to float, and may end up running aground if you anchor in water that’s too shallow when the tide turns. Credit: JPWallet

Do catamarans and trimarans need keels?

Unlike monohulls, multihull vessels (like catamarans and trimarans) don’t feature ballasted keels, and instead rely on their wide beams and increased buoyancy for stability in the water. Without keels, they’re able to float in shallower waters, can take the ground safely, and are often far more lightweight for faster sailing. However, without that additional ballast beneath the hull, multihulls won’t self-right the same way a monohull will. This basically refers to a monohull’s ability to right itself after heeling in a strong gust. Obviously, with a wider base, it will take a lot more to turn over a multihull than a mono, but once a multihull has been tipped over, it’s almost impossible to right the ship again! That said, without the extra weight, an upside-down catamaran will generally be able to float in that configuration, which is why you’ll often see ‘escape hatches’ in the floor of these vessels – giving a capsized crew a route onto the new ‘deck’. Similarly, when a monohull keels over, it effectively spills some of the wind, allowing it to ‘shake off’ excess force. Without keels, this isn’t possible on a catamaran or trimaran, so sailors on these types of vessels will need to be more vigilant when it comes to trimming sails and manually spilling those big gusts.Do motorboats have keels?

Some motorboats might have a keel, but they’ll generally be long and shallow, if they have one at all. Motorboats don’t need keels generally because they rely on their engine for propulsion, rather than the opposing forces of the wind and lateral resistance of the water on the keel. By adding ballast to the bottom of the hull, the main advantages of a keel are redundant when travelling under engine power, while getting rid of them means the boat can travel faster, manoeuvre easier, and access shallower water. That said, if the boat isn’t designed to go faster than hull speed, a motorboat may have short keels on either side to give them a bit of extra stability in strong winds, much like the leeboards on a Dutch barge. But the hull shape of motorboats can vary greatly for lots of very clever reasons – this would be a whole other article! It’s worth noting that, although few motorboats have keels in the way we’ve described them here, the design and shape of motorboat hulls can vary greatly for all sorts of very clever reasons – but to discuss them would require a whole other article (and probably an engineering degree)!

Because motorboats depend on their engine, instead of the wind, to propel them forward, they follow different rules to sailboats and usually don’t need a keel. Credit: GuyNichollsPhotography

What keel is best for me?

As we’ve discussed in this article, the type of keel you select for your next vessel can dramatically influence what you’re able to do with it and where you can take the boat. So, there’s no black-and-white answer as to what type of keel is best. However, asking yourself some of the following questions may help you figure out if the boat you’re looking at will perform in the way you want:- Are you looking for speed?

- Are you looking for comfort for a long passage?

- Will you be sailing in shallow waters?

- Do you want to be able to beach the boat?