Learning the hard way on tidal rivers!

Patience may be a virtue required of all aspiring tidal river dinghy cruisers, if like me, they inevitably temporarily strand themselves on mid-channel sand banks or margin mud flats. Sailing some of my tidal rivers along south Devon’s spectacular coastline is an enjoyable but at times ‘fraught’ experience. From rapid short tacking up narrow channels in variable winds and sudden becalming on the outside bends of meanders to being spun backwards in eddies and turned broadsides across river channels, I’m beginning understand that making the best use of a tidal river’s characteristic features is paramount to achieving easier, faster and more enjoyable upriver sailing. Suffice to say, learning to sail on RYA 1 and 2 courses in the Med never prepared me sufficiently for the vagaries of the upper river channels on the Tamar, Lynher and Dart.

As in many aspects of life, preparation is the key to success and so ‘pre-cruise weather interpretation’ is vital (Tip 1). The frightening broadside encounter in steep waves passing over the bar at the entrance to the River Avon near Bigbury, in strong southerly winds on a rapid early flood spring tide, could have been avoided if I’d consulted local DCA members and a regional almanac beforehand (many advising a ‘safe approach’ towards the top of the tide along the deeper water channel on the western shoreline!) Visiting the river entrance many times over the years is not the same as sailing into it! A year on and I still have occasional nightmares about that ‘broaching’.

There was that sudden becalming and drift backwards at high speed on the outside of the fast-flowing meander bend above Weir Quay on the river Tamar – it taught me the value of ‘proactively anticipating pilotage problems’ whilst sailing up rivers in light, variable winds. The ‘unanticipated’ frustratingly slow upriver sail against increased river flow on the upper Dart after a period of prolonged rainfall, led to lots of subsequent hull ‘ding’ repairs caused by ‘unseen’ washed down tree debris; whilst unforeseen low flow and shallower depths of water to the upper river Tiddy during one long hot summer meant I didn’t reach the uppermost creeks on that trip either!

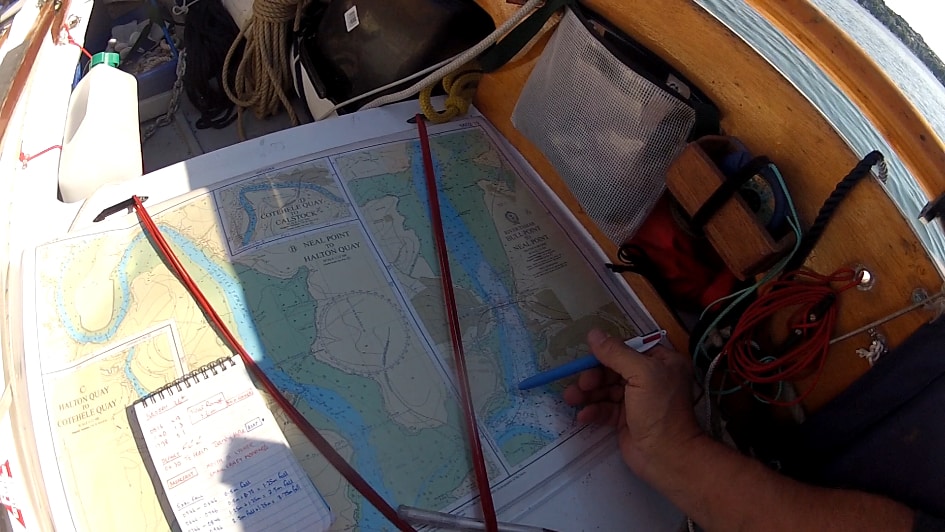

Spend time anticipating pilotage hazards and resolutions in advance (tip 2). Pre-trip reconnoitring potential hazards on Google Earth and local charts is one of life’s little joys. Wind shadow areas, the effect of topography on wind direction, rapidly shallowing mid channels and the uncharted channel edge rows of oyster racks can all pose dangers. Pre-voyage hazard spotting pays off as some hazards require fast decision making with little time to study charts on an open boat thwart when actually negotiating the narrowest river channel!

To this end, I create simple annotated channel maps and pilotage notes in a small waterproof notebook for quick reference as I sail a particular stretch of river (tip 3). Notebook in one hand and tiller and mainsheet in the other, I spend more time looking out of the boat ahead than down to the charts on the thwart. My sailing course decision making and anticipation of possible hazards thus improves. Table one lists the kind of annotations I write around my notebook sketch maps and I hasten to add they aren’t all added on every map – keep it simple!

Annotations around my sketch maps

- Potential wind shadow areas, e.g. shoreside woodlands, buildings etc.

- Channel depths and mid channel sand bar positions.

- Buoyage marks.

- Aspects fo typography, e.g. hills, side valleys.

- Tidal information - heights, ranges, drying out depths and times, best times for entering tributaries, leaving quaysides etc.

- Bearings and distance between naviagtion marks.

- Possible transit lines.

- Hazards e.g. low bridges, crossing powerlines uyster racks etc.

Of course, my notebook isn’t a substitute for carrying quality charts and chartwork equipment. It’s for holding in my hand as a rapid aide-memoire and every night on a dinghy camp cruising voyage, the notes are checked against next day’s weather forecast and amended accordingly. I am, as some of you know, a permanently ‘paranoid’ dinghy cruiser!

Successful tidal river voyages, I soon discovered, require some understanding of river flow dynamics and evolving channel features (tip 4). Sinuous channels can alter flow patterns so potentially impeding upriver passages. Run with the incoming tidal stream mid-channel where river flow tends to be faster for quicker upriver journeys. Slower flowing shallow water on straight channel sides offer best chances for quick progress upriver against an ebbing tide, but try not to ground yourself, as I have done several times on the shallow river beaches on the inside of meander bends! Deeper water on the outside of a meander bend where faster currents scour a deeper channel, may bring safe depths but also, of course, faster flow towards you, which slows your boat’s forward progress. Go on – ask me how I know! Use the flood tide for an assisted push on that upriver outside meander bend passage!

On the upper rivers Tamar and Dart are many margin reedbeds. On a lee shore, Arwen’s bow wave runs against the reeds, meets resistance and so creates extra water lift, thus providing a couple of extra boat lengths upriver progress parallel with the reeds before we have to put a new tack in (tip 4a). Resisting that panicky urge to tack away, I’m rewarded with some fantastic glimpses of wildlife in the reed beds as well. Yes, occasionally I miscalculate, the centreboard hits bottom, Arwen stalls and I have to oar push her off the mud/reeds!

Of course, my notebook isn’t a substitute for carrying quality charts and chartwork equipment. It’s for holding in my hand as a rapid aide-memoire and every night on a dinghy camp cruising voyage, the notes are checked against next day’s weather forecast and amended accordingly. I am, as some of you know, a permanently ‘paranoid’ dinghy cruiser!

Successful tidal river voyages, I soon discovered, require some understanding of river flow dynamics and evolving channel features (tip 4). Sinuous channels can alter flow patterns so potentially impeding upriver passages. Run with the incoming tidal stream mid-channel where river flow tends to be faster for quicker upriver journeys. Slower flowing shallow water on straight channel sides offer best chances for quick progress upriver against an ebbing tide, but try not to ground yourself, as I have done several times on the shallow river beaches on the inside of meander bends! Deeper water on the outside of a meander bend where faster currents scour a deeper channel, may bring safe depths but also, of course, faster flow towards you, which slows your boat’s forward progress. Go on – ask me how I know! Use the flood tide for an assisted push on that upriver outside meander bend passage!

On the upper rivers Tamar and Dart are many margin reedbeds. On a lee shore, Arwen’s bow wave runs against the reeds, meets resistance and so creates extra water lift, thus providing a couple of extra boat lengths upriver progress parallel with the reeds before we have to put a new tack in (tip 4a). Resisting that panicky urge to tack away, I’m rewarded with some fantastic glimpses of wildlife in the reed beds as well. Yes, occasionally I miscalculate, the centreboard hits bottom, Arwen stalls and I have to oar push her off the mud/reeds!

Back eddies on the inside of the large meander above Weir Quay on the river Tamar sometimes get me around the bend more quickly (tip 4b). A local salmon netter advised me that “on a rising tide, downstream flow comes up against the incoming tidal flow creating little back eddies in your favour”. Last trip, this worked. I now dangerously assume that the ‘inside bend eddies’ idea might be applicable to other river meanders, a theory to be tested soon on the River Dart!

Back eddies on the inside of the large meander above Weir Quay on the river Tamar sometimes get me around the bend more quickly (tip 4b). A local salmon netter advised me that “on a rising tide, downstream flow comes up against the incoming tidal flow creating little back eddies in your favour”. Last trip, this worked. I now dangerously assume that the ‘inside bend eddies’ idea might be applicable to other river meanders, a theory to be tested soon on the River Dart!

My centreboard is my depth sounder (tip 5) in my part of the world where it is easy to become disorientated when rising tides cover extensive mudflats or mid channel sand banks. Notebook channel sketches become meaningless and I’d often unwittingly stick to the middle of the wide channel for a false sense of safety; shamefully not really knowing which side of me deeper water was to be found. After many, many groundings, I’ve learned to ‘spot’ the shuddering bounces of my centreboard on the channel bed below but sadly not which way to turn for deeper water. This coming season, perhaps a 6’ bamboo cane marked off in 1’ intervals might be my new ‘best friend’ (thanks to Dylan Winter of ‘Keep Turning Left’ fame). Lying securely along one of the side decks until needed, it might be a useful creek crawling aid. Watch some of Dylan’s YouTube videos to see how easily he places, retrieves, reads and then re-plants the cane as he sails shallow creeks. It seems very effective in narrow shallow creeks but there again, I may be just overthinking things and it isn’t really required!

Tip 6 is to become proficient at calculating minimum tidal depth requirements and tributary entrance times for different parts of your river passages. Too often lulled into a summertime ‘drift stupor’ by stunning scenery, bright blue skies and gentle warm breezes, I’d jump the gun by starting up a river tributary before sufficient tide had built and then spend time sitting on a mud flat waiting for more water depth. A quick glance at my notebook ‘calculation’ annotations now refocuses my attention. Become adept at recognising the clues to decreasing water depth ahead (tip 7) - those isolated mid-channel reed patches, the static clumps of floating surface seaweed, the locally planted vertical withy canes or the little twigs emerging skywards that betray the presence of submerged branches trapped on mudbanks below.

Think vertical height as well as depth beneath (tip 8). The horrible crunch, accompanying shower of leaves and twigs from above and the sudden drop in hull speed as I rounded the final bend before Calstock served as a late reminder of the hazard of overhanging tree branches. Woe is the sailor failing to correctly calculate tidal depth range and mast clearance heights on entering the Tamar’s tributary, the Tavy. Trust me, that railway bridge is much, much lower than it first looks. Too much tide beneath you and, well you get the picture – go on – ask me how I know!

I hesitate to share this, but it sorts of links to tip 10 in a way. Last season, I became acutely paranoid, sure that winds were always conspiring against me. Their sudden last moment shifts to blow directly towards me down particularly narrow channels, led to some seriously challenging short tacking upriver (and time spent beached on creek margins!) Worse, were those frustrating, sudden, unanticipated becalmings. Learn to ‘expect the unexpected’ where river winds are concerned (tip 11). Local topography often funnels them up or down river valleys. On the westerly running lower river Lynher, for example, I find long tacks into headwinds are the norm, even if the nearby prevailing coastal winds are south easterlies. Losing ground constantly one day, having battled headwinds and chop for a long time, I realised it wasn’t a ‘sailing failure’ to just anchor up temporarily to await more favourable conditions (tip 12). A daft notion I know but overcoming it led to a pleasant 40 minutes admiring the scenery and mudflat wildlife whilst waiting for tidal flow to build sufficiently to give me the extra push to overcome the river flow and headwinds. Similarly, watch out for wind against tide choppy conditions - coming down the Tamar one time in a hurry, on a rapidly ebbing tide, directly into strengthening prevailing south westerly winds caused damage to my outboard bracket and transom, a nasty bout of sea sickness and lots of spray water collecting in the bilges.

Winds will sometimes cross rivers at near right angles and in such places, I found one tack across the channel ended up being longer than the other return tack. These longer tacks afforded more progress upriver but always ended on a lee-shore, so depth watching was critical. Over cautious, I’d often tack early to avoid grounding myself on the exposed fringing mudflats. Try to resist that urge (tip 13)! On shorter tacks to windward, leave the tack until the very last moment and use the extra lift on a weather shore to gain a few metres parallel with the shoreline before putting in the next tack. I escaped the occasional grounding by immediately backing the jib to gain sufficient leverage to re-float and set off on the new tack.

Anticipating potential wind shadow areas on tidal river passages is time well spent (tip 14) but alas, I’m useless at it. Decisions on how to pass through them are best made before arriving in them and it is part of my routine pre-voyage research. Often becalmed at Dandy Hole, a sharp dog leg bend to the north on the river Lynher, where wooded steep hillslopes dampen the prevailing south westerly winds, I discovered by trial and error that my best chance of finding wind was to sail two-thirds of the way across the channel from the wooded shore on the outside of the bend. Wind shadow areas apparently widen out the further they are from the obstruction causing them – go figure. Passing close beneath the wooded hillslope resulted in no wind and a fast-flowing current. On the far channel side, skirting the little Redshanks beach spit area, wind always seemed disturbed and variable as it reflected back off this opposite shoreline. Two-thirds across from the woods, Arwen seemed to catch the breeze each time.

In actively seeking out those surface water wind ripples, I need to remind myself that rivers aren’t the same as the deep-water Plymouth Sound (tip 15). After many mid-channel sand-bank groundings I’ve eventually remembered ‘depth’ before heading for the wind ruffled water. Some lessons are so painful to learn!

Talking of hard lessons on the water, remember the importance of proper sheet management (tip 16). Should you never cleat your sheets when river cruising to make sure they can run out fully without catching on something and what about the number of times I’ve eased the main sheet to spill wind during a sudden gust only to find I’m standing on the surplus sheet on the cockpit floor? A tidy cockpit with surplus sheets and halyards stowed away properly seems essential. Then there is that ‘irritating’ slowness of wet mainsheet running through aft tackle blocks hampering the mainsail movement during an ‘urgent’ tack, all because I’d let sheets fall from the aft boom to drag lazily in the water whilst on a previous reach! Water on the floor and a slow mainsail switching sides is a recipe for disaster and it is only recently that I have discovered the joy and versatility of holding a limp falling mainsheet from the boom in my hands. Pulling the mainsail sheets back and forth across the boat rather than hauling them through the block when tacking was a revelation. It made tacking passages up narrow channels so much easier.

I am in awe of the old 19th century Tamar barge skippers who ghosted large boats upriver in light winds, stemming the shallow river flow and delaying tacks to gain some additional precious forward momentum parallel to the channel edge. Having spent much time temporarily grounded on mudflats making new friends amongst the ducks, herons, geese and egrets, through perseverance, I’ve learned to keep my way on by getting extra speed and good water flow across rudder and centreboard (tip 17). Tacking for speed rather than upriver progress reduces downstream sideways slippage and enables me to point up head to wind at the last moment in the shallows, where I then carry some extra upriver forward progress parallel with the channel margin. I think I read somewhere that over in East Anglia barge skippers call it ‘huffing’.

And there we have it. This is what I have learned so far as a novice dinghy cruiser tackling my local tidal rivers. All rather pitifully obvious I suspect but sometimes ‘you just don’t know what you don’t know’. Ideally, all my forthcoming river trips will now be on flooding tides after a few dry days, with constant unshifting winds from astern and as high water is later the further upriver you go on the Tamar (tip 19), I will get longer to sail upriver and enjoy the scenery, wildlife and industrial archaeology of this world UNESCO heritage valley. But, in reality, you and I both know that days like these when all the elements positively align will be rare indeed, in which case I’m bound to need some of these newly learned skills!

And there we have it. This is what I have learned so far as a novice dinghy cruiser tackling my local tidal rivers. All rather pitifully obvious I suspect but sometimes ‘you just don’t know what you don’t know’. Ideally, all my forthcoming river trips will now be on flooding tides after a few dry days, with constant unshifting winds from astern and as high water is later the further upriver you go on the Tamar (tip 19), I will get longer to sail upriver and enjoy the scenery, wildlife and industrial archaeology of this world UNESCO heritage valley. But, in reality, you and I both know that days like these when all the elements positively align will be rare indeed, in which case I’m bound to need some of these newly learned skills!

Video vlogs about my cruises along the rivers Lynher, Tamar, Yealm and Kingsbridge estuary and about dinghy cruising in general, can be found here.