Lindisfarne always feels like home even though I live miles away in the city. Driving down the narrow road which cuts through the dunes to the start of the causeway fills me with happiness. Every time I arrive here my heart skips a beat where the view opens out to sand stretching as far as the eye can see under a huge Northumberland sky.

The seaweed-covered causeway which runs across these sands is exposed at each low tide allowing cars to drive onto Holy Island, the tourist name for Lindisfarne. I pull into the long layby and park up so I can read the SAFE CROSSING TIMES notice, to double-check it is still safe to continue before the road vanishes beneath the sea.

Towed behind the car is my Wanderer dinghy, designed and fitted out specifically for coastal sailing. She is my pride and joy and I feel so excited this weekend as I attempt to complete one of my sailing dreams.

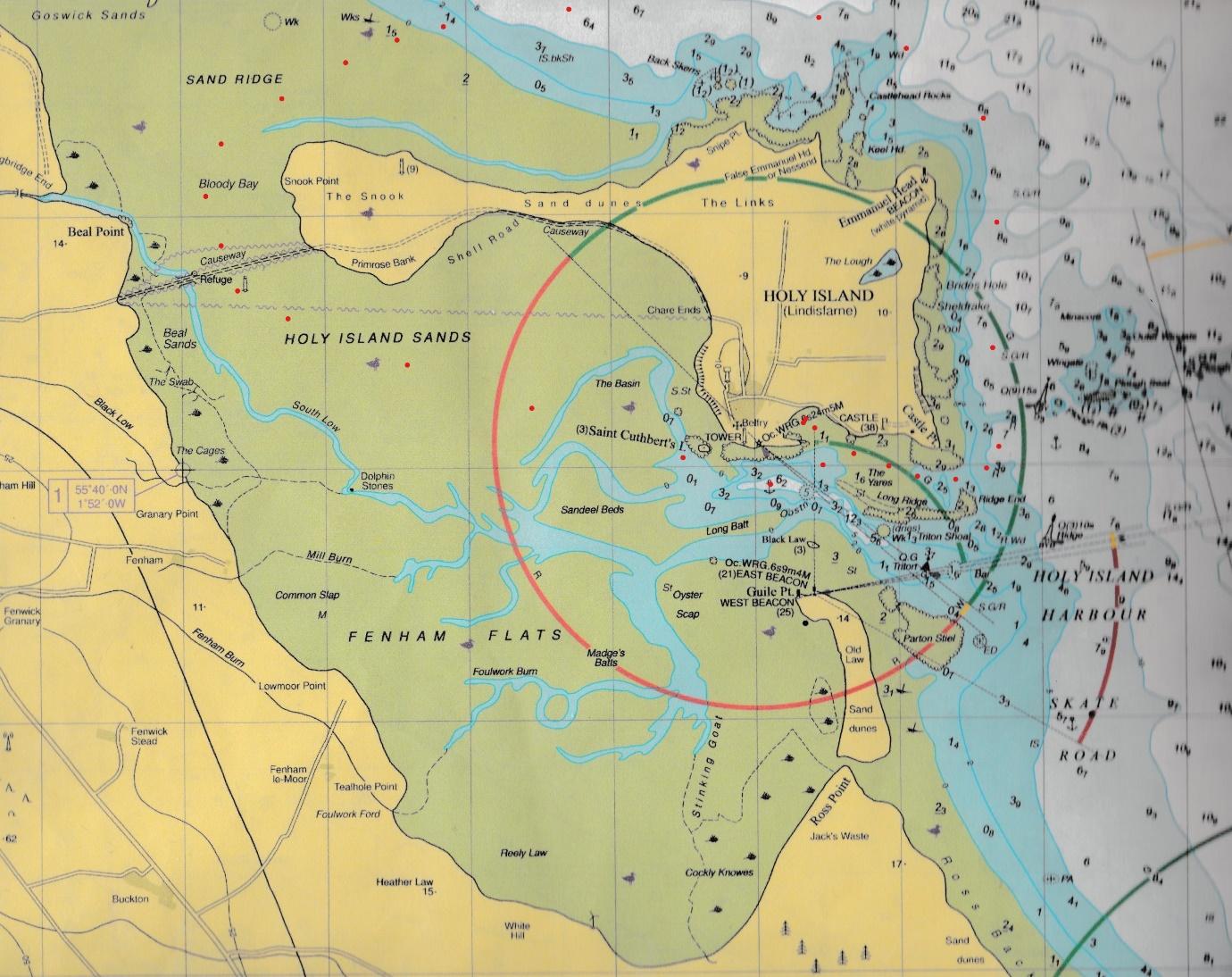

It is Autumn and already the nights are drawing in. The Harvest Moon will soon appear over the horizon creating an enormous spring tide, the largest of the year with a height of 5.2 metres above chart datum. My aim is to use this tide to circumnavigate Lindisfarne Island, sailing over the same road which I am about to drive across. This can only be attempted once every year.

The Ouse is the name given to the island's harbour which remains an active fishing port with 4 brightly painted trawlers bringing home a daily catch. I launch here, weaving between the small fleet of moored fishing boats until I meet the strong tide flooding into Fenham Flats. Soon I am surrounded by large Atlantic Grey seals, their size makes their playfulness feel a little intimidating as they surround my tiny boat, curious yet scared, they follow my track northwards.

My watch tells me it will soon be high water, I feel the need to press on. Alone at sea in a 14ft sailing dinghy with a forceful tide and a fresh breeze filling the sails makes me excited, maybe a little anxious as I set out on this micro-adventure. I love this type of sailing the most. The freedom and risk of going alone, taking responsibility for every move I make. My boat glides silently past St. Cuthbert’s Island heading towards the first waypoint, a refuge tower standing on tall stilts above St. Cuthbert’s Way where people walk across the sands from the mainland at low tide. When I arrive, I find only a small barnacled section of each stilt remains above the sea; it will soon be high tide.

I need a slow and cautious final approach to the causeway because the causeway is marked by tall steel posts which are now invisible, submerged just below the surface of the rising sea. In addition to this hazard is the road itself. Raised above the sand at around 4 metres above chart datum, there will be only just sufficient depth to cross at high water today!

Both wind and tide are pushing the boat along at 5 knots. I beat back and forth, holding my position, unsure whether I have sufficient depth to cross. One final check of my watch confirms it is time to make my attempt. I return to the reference point, the stilted timber refuge, make one final tack, ease the sheets and head straight for the road sign I checked out earlier from my car.

The sea below is murky, a mixture of sand, mud and water churned up by the flooding tide. I sense the shallowness, so raise the centreboard protecting it from possible impact with the seabed. My next waypoint is the SINGLE FILE TRAFFIC road sign which now appears to be floating on the water, the waves lapping at its lower edge with the supporting pole totally submerged. I need to pass only metres from this sign otherwise I risk running my dinghy into the steel posts lurking just below the waves.

My GoPro records the final moments and within seconds I sail over the road. I’ve finally done it! All my planning has worked out. The late nights studying charts, tide tables and the addictive analysis of weather forecasts these past few days has paid off. I have achieved another one of my sailing goals.

Glancing over my shoulder I see a small queue of cars waiting in the layby on the mainland, drivers stood gazing over the sea towards a small sailing boat gliding over the flooded causeway. I wave to them triumphantly and laugh to myself thinking what a picture it would make from their viewpoint.

Lowering the centreboard fully, I regain speed by adjusting the sails, the breeze feeling stronger now. Suddenly something catches my eye. A tilted pole protrudes from the sea only a few cables away and I am approaching it rapidly on this broad reach. I quickly check the chart folded in a waterproof sleeve and see the wreck clearly marked. How could I forget this? My focus on the road crossing has deleted from my memory the remainder of the passage, which is only half complete.

I steer to starboard and check my notes. The water here will be just as shallow as the causeway, so I raise the centreboard once more. Passing close to the wreck I notice some withies not shown on the chart. I feel worried seeing these but reason that nobody sails here except adventurers in dinghies so guess these sticks have another purpose and ignore them.

The northern part of Lindisfarne is wild and remote, out of sight from everyone on land. Ahead the open sea awaits with a continuous line of surf marking the underwater boundary between shallow and deeper water offshore. As I approach the surf-line I begin to realise the height of the waves rolling in from the sea, but there is a small line of weakness where a rip is flattening out the surf. I steer towards this point without breakers.

As I clear the northern tip of Lindisfarne my boat accelerates downwind towards the surf. Large tubes either side roll and collapse with thunderous noise as my bow heads up the first wave. The speed I reach over the top is quite alarming, but my boat remains balanced and sure as each wave in succession flows smoothly by.

The open sea has large swell and the turning tide is starting to push against the breeze. My Wanderer powers south along the rugged coast, sails sheeted in and heeled hard on the chine. Emmanuel Head with its sandstone cliffs and white pyramid are soon abeam with my little boat dancing through the waves. Wanderer dinghies were created for this type of sailing and so was I.

Photo by Jim Sumo

Within an hour of breaking through the surf barrier I can see the impressive ramparts of the castle, standing proud overlooking the North Sea. This is the landscape Vikings encountered centuries ago after their sail from Scandinavia. I feel like a real explorer as I clear the castle headland and turn hard to starboard before Ridge east cardinal buoy, its white light flashing in the fading light. The home run into the harbour is joyous. I have a warm glow inside, weaving between the fishing boats until safely inside the harbour wall. In the twilight, village lights sparkle in the calm harbour water at my journeys end. I wonder how many other roads there are in the world I can sail over.

Small boat coastal sailing is a truly emotional experience. The feeling of freedom is immense once you venture into the open sea where wildlife surrounds your boat as you silently pass through their world. Dinghy sailing is physical, stimulating and rewarding. Most of all, sailing my Wanderer dinghy has opened doors into the sailing world where my experiences have been applied to larger vessels and ultimately led to my Yachtmaster qualification and work as a yacht instructor.

If you want to experience this type of sailing, RYA Level 3 courses in Seamanship and Day Sailing are designed to teach coastal sailing skills in small boats. They say good dinghy sailors make great yachtsmen.